What If The Obvious Isn't Obvious?

The Strange Surprise Of Obviousness

I was reviewing some changes a colleague had made in a Power BI report. As part of this, they had created some new DAX measures. The logic used was reasonably complex involving CALCULATE, FILTER and nested IF statements. It was technically correct but deciphering it was like trying to untie a knot in the dark!

"This works perfectly" I said "but it took me a while to get my head around it and understand what it was doing. Next time a tiny trick I use is to add a comment at the start of the measure. Just a couple of lines explaining its purpose. Just helps with cognitive load for anyone reading it at a later time"

They took a pause and then with genuine surprise "you can do that?" They carried on: "that would be great, sometimes I return to measures I've written months later and forget what they do!".

I was shocked. Not in a "how could you not know this??" way but more in a disorientating way like someone who always pushed a door open with their shoulder because they'd never heard of a door handle.

This wasn't Best Practice. It was what I considered basic professional hygiene almost as automatic to me as breathing. And yet to a skilled, competent colleague, it was a revelation.

It made me reflect: what if the obvious isn't obvious?

The Craft Gap

The moment revealed what I call the "Craft Gap". It's not a gap in skill, but a gap in focus and incentives.

Many teams are rewarded either explicitly or implicitly for speed, being able to ship new features fast or learning on the fly. In these environments the small details that make work maintainable, understandable or delightful are often the first to be left out in favour of speed. They are silent, invisible costs that cannot be measured and don't show up until much later.

The practices I took for granted such as commenting code, ordering objects into folders, considering the user aren't about being pedantic or stuffy. They are born from a different set of values: empathy for myself and for the next person who will touch the code or the report. They are a form of investing time now to save a greater amount of time and frustration later down the track.

And this approach has been learnt the hard way, I wasn't born like this. I found myself untying knots in the dark far too many times, often knots of my own making. I didn't enjoy being in those situations so I learnt to be defensive in my development work and put these preventative measures into practice.

This isn't about craftspeople versus everyone else. This is about recognising that we all, based on our experiences and what our environment rewards, have different "obvious" practices.

Why This Matters (and How It Shows Up)

These aren't funny little quirks that some developers have. They are the key blocks to building and maintaining a sustainable, humane, robust data product. Examples include:

Naming and documenting things clearly

As mentioned if I document my code, I can pick it up again in future and understand why it was created in the first place and how it works. I'm immediately up to speed. Even within code, if the variables used are named well, the code documents itself. Variables such as _UsersWithTargets or _SelectedKPI don't leave any doubt as to what value they are storing. Far more intuitive than, say variables such as _Table or _SummaryUsers

In the report, if we have a card that says "Last 12 Months", do we know what period this relates to? Is it complete months? Does it include the month we are currently in?

Refactoring logic for simplicity

Using variables is a good example here. Some DAX developers believe that the shorter a measure is, the faster it will run. However this is not true. And splitting out complex code by storing intermediate steps in variables can sometimes make a measure run faster. It will certainly make it clearer and simpler to understand for the next developer.

Considering the user's viewpoint, even if it is an internal user

I know what this card displays or what this visual displays but that's because I built it. What about Janine in Accounts who will actually be using this report? Does she understand? Is it written in plain English or is it data / business jargon? Does it make sense, given her view of the world?

Asking 'Why?' before building

Understanding the end goal before putting a spade in the ground is crucial. Simply by asking the stakeholder to expand ('tell me more') or asking them to explain in plain language what they want and what success looks like to them can make a massive difference in terms of development approach or time taken.

Logical Grouping of Folders in Power BI

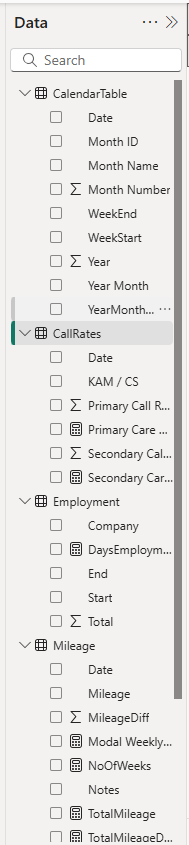

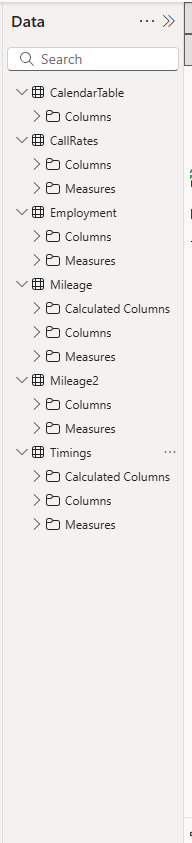

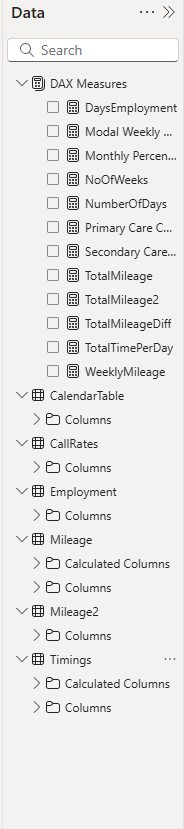

When working in Power BI, the number of objects that appear in the Data pane increases rapidly which can make it hard to find the measure or the column you need at any particular time:

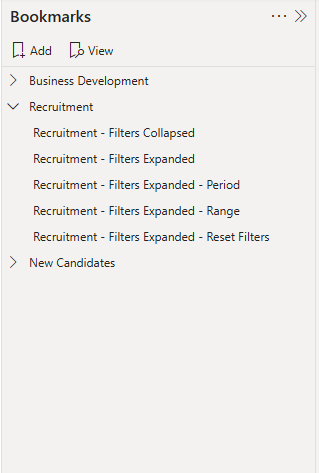

This sort of organisation does not just apply to the Data Panel. It can also (and I would argue should also) be used in the Selection Panel and the Bookmarks Panel as below examples show:

The Humility of the Obvious

This gap isn't a measure of intelligence, it's more a reflection of experience and values. My colleague is highly skilled in areas I'm not. The revelation wasn't that I'm smarter. It was that what feels obvious to me is because of a specific set of values and experiences - empathy for myself and for the next developer - that I had never thought to articulate.

This is the heart of the craftperson's dilemma: The very practices that ensure long-term quality are often invisible and are therefore the first to be sacrificed to the God of speed.

We don't celebrate the avoided crisis, the hour not wasted deciphering code or the user who felt good using the interface. We only celebrate the shipped feature. The most valuable parts of our craft are often the quietest and hardest to recognise.

Making the Invisible, Visible

That conversation with my colleague made me realise what I take for granted in my day to day work are not just personality quirks. They are a silent language. A language of care, thoughtfulness and quality that often goes untranslated.

I no longer assume the door handle is obvious. I now point it out sharing these small practices not from a place of superiority but from the understanding that we have all, at some point, been pushing the door with our shoulder unaware that there was a better way.